Lace up your boots. Get your hard hat on. Throw on your pack and parachute into where the mountains are burning.

That’s the job of the smokejumper — a skydiving firefighter considered the elite special operations arm of firefighting.

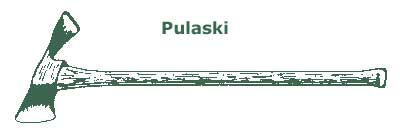

Comprising only three percent of America’s wildland firefighters, they are the tip of the spear — or the Pulaski— called into action to tackle wildfires in remote areas.

And they’re doing the job alone.

Once the alarm is triggered, smokejumpers grab their gear and hop on a plane to race toward a wildfire, typically in the rugged mountains of the American West. The jumper’s primary mission is to leap from a plane, land somewhere close to the blaze, and then execute a quick initial attack on the inferno.

Once the fire is spotted, and a relatively safe landing zone is selected, the smokejumpers exit the plane with over 100 pounds of gear strapped to their bodies.

If the crew has survived the drop without injuries, they immediately begin work “punching the line.” This is smokejumper slang for creating a firebreak, or zone that cuts off the fire from its fuel source. The crew accomplishes this through back-breaking work by cutting brush, felling trees, and digging trenches in the ground ahead of the fire.

Since smokejumpers cannot predict how long they will be attacking a wildfire, they jump with enough equipment and supplies to sustain them for the first 48 hours on the ground.

Each jumper has a parachute, reserve parachute, parachuting harness, and a gear bag that dangles between the legs and converts into a backpack once on the ground. A helmet with a protective face cage is worn during the jump to ward off tree branches during the descent. That is replaced by a second helmet at the fire to protect from falling objects. Many also carry a 100’ let-down rope in an exterior pocket in case they get hung up on a tree.

Smokejumpers wear flame-resistant pants and shirts. Typically made from Nomex, this material isn’t 100% fire proof, but will burn if exposed to flame and stops burning once the flame is removed.

Next is a high-collared padded jumpsuit. Lined with Kevlar for puncture resistance, the jumpsuit is worn over their clothing while parachuting to the ground. The jumpsuit is also covered with pockets to stow radios, clothing, and smaller tools. A few jumpers even stick a frozen steak in a pocket to eat later.

Smokejumpers also wear specialized boots to handle extreme heat while still providing mobility and stability. Stiff leather is used in the boot’s insole and heel to maintain its shape while walking over uneven terrain. Leather arches prevent excessive bending and heat insulation.

In addition to two days of food and water, smokejumpers carry personal fire shelters in their backpacks. Resembling foil-like survival blankets, the fire shelter is made of aluminum foil, woven silica, and fiberglass. If a fast-moving fire is about to overrun the crew, each member deploys a fire shelter. The fire shelter reflects radiant heat and traps breathable air inside, protecting the smokejumper for up to an hour.

Without trucks to store and access heavy equipment, smokejumpers mostly rely on hand tools to control wildfires. The Pulaski is a traditional axe modified with an arched blade, or adze, on the opposite side. The adze is used to break up topsoil, while the axe chops roots and brush. A McLeod is another two-sided tool with a long handle. One side is a sturdy metal rake, and the other is a sharpened blade. Smokejumpers also carry crosscut saws on the initial jump.

Heavier equipment like chainsaws, pumps, hoses, fuel, and food is typically airdropped to the crew via paracargo.

Smokejumpers can trace their origins to firefighters who started exploring using parachutes to quickly attack wildfires in the early 1930s. The thought was that airdropped self-sufficient crews could reach the fire line in better condition if they weren’t fatigued by strenuous and lengthy hikes. Initial tests with small two-man teams were successful, so the concept soon became a full-blown program and tactic.

More than 200 workers from Civilian Public Service camps worked as America’s early smokejumpers fighting fires throughout west-central Idaho during World War II. Bases of operation were soon established in McCall, Idaho, and later Missoula, Montana.

By 1944, the U.S. Forest Service had created a permanent Smokejumper Project to train and deploy professional skydiving wildland firefighters.

A year later, the famed 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion was sent to the West Coast to fight fires created by Japanese incendiary balloons.

As the only black airborne unit in the U.S. Army, the troops were never sent to combat but were instead tasked with dealing with the threat of Japanese incendiary balloons meant to start forest fires. Since the balloon attacks never fully materialized, the troops were reassigned as smokejumpers to fight wildfires throughout the Pacific Northwest.

During their tour of duty, the 555th made more than 1,200 jumps.

In October 1945, the 555th was transferred to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, its home for the next two years.

Based on their strong reputation and abilities as Paratroopers they were soon attached to the 82nd Airborne where they once again made history as the 82nd “All American” Airborne Division became the first integrated division of the US Army.

As experience was gained and technology advanced, today’s smokejumper is the product of a more specialized and rigorous training pipeline.

Candidates must have years of wildfire-fighting experience and be in peak physical condition. One component of their fitness test is successfully carrying a 110-pound pack for three miles in 90 minutes or less.

Once selected, candidates must complete jump training, including knowing how to land on uneven terrain and parachute maneuvering. Smokejumpers also become expert riggers and tailors. One of the first things many rookie smokejumpers learn after their initial jump training is how to sew. They sew their own parachutes and make their own jumpsuit and gear bag that converts to the backpack. After completing their mission, most crews must carry all their equipment back out on treks that sometimes last a few days.

Since the American west has gone from fire seasons to fire years, smokejumpers have continued to be called upon with increasing frequency to fight larger and more intense wildfires.

Currently, there are about 400 smokejumpers dispersed among nine crews stationed in the west. These brave men and women continue a proud legacy of fighting one of Mother Nature’s most potent elements armed only with a Pulaski, dirt, and an abundance of courage.

A good friend in Medford was a jumper. Good human. Badass. He was the one that convinced me that every homeowner needs a pulaski. He was right.

One of my all-time favorite books is “Young Men and Fire” by Norman Maclean (yes, the River Runs Through It, Norman Maclean). It was his magnum opus and the research for it consumed many of the last years of his life. Have read it a couple of times, and ironically just finished the Audible version today, and then got the PDW email with the link to this article. Got that book when it came out in 1992.

Norman’s son wrote a similar book about the 1994 South Canyon/Storm King fire that killed most of a hotshot team from Prineville, a jumper, and others. Also a good book.

Thanks for this one.