From Baffin Island, Franklin headed west and made it to Beechey Island, about 475 nautical miles north of the Arctic Circle, before the pack ice forced the expedition to a halt.

That first winter, three crew members, Royal Marine Private William Braine, Able Seaman John Harkness, and Petty Officer John Torrington, perished.

Their graves wouldn’t be discovered for another 10 years, and it would provide the first clues as to the Franklin expedition’s fate. Their bodies were exhumed in 1984 and 1986 with scientists concluding Torrington had died of pneumonia, while Harkness and Baines succumbed to pulmonary tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis, a bacterial lung disease that is easily spread through the air, was rampant in the 1800s. Cramped conditions on board the Erebus and Terror are believed to have led to its rapid spread among the crew, further crippling their effectiveness.

The following summer, when the ice finally opened enough to allow the ships to move, Franklin headed south through the Peel Sound. The expedition made little progress before becoming once again mired in the pack ice on September 12, 1846, off the northeastern shores of King William Island.

With the ships ice-bound a second time, Franklin could do nothing but wait until the summer of 1847 for the pack ice to break.

Not much is known of what transpired that winter.

The following spring, Franklin’s first lieutenant, Graham Gore, wrote a brief note describing the expedition’s location and concluded with the words “all well” in May 1847.

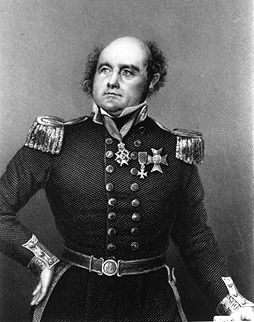

A month later, Sir John Franklin was dead.

There is not much information on what happened from that point onward except for one damning fact: Summer never came to the arctic in 1847.

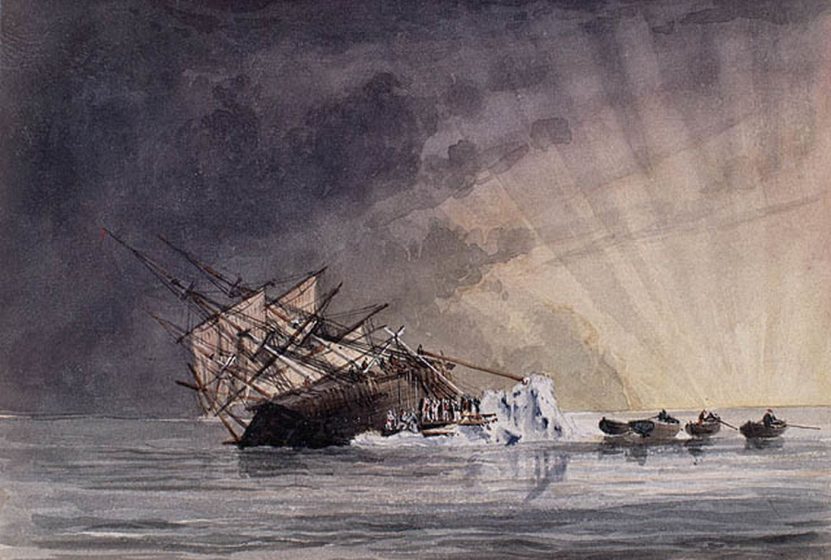

The pack ice was never going to free the Erebus and Terror.

Franklin’s decision to sail down the west side of King William Island put both ships through a (now) well-known area where the ice is often not clear in the summer. In fact, the first explorer to successfully navigate the passage by ship, Roald Amundsen, did so along the island’s east coast in 1903-1906.

The surviving crew, now under the command of Crozier, spent a third winter locked in the ice as the flow carried them farther off course.

By this point, a dwindling food supply and hostile environment, where temperatures were -30°F by day and could drop to -54°F overnight, were taking their toll.

Many men were suffering the effects of scurvy: loose teeth, bleeding gums, bruising, and shortness of breath. Even though the crew was issued one ounce of lemon juice a day to fight off the disease, it didn’t appear to be working.

Lemon juice’s active ingredient is ascorbic acid (vitamin C), which becomes unstable with prolonged storage. Anthropologists believe the juice likely fermented. To prevent further fermentation, the crew may have boiled the lemon juice, thus destroying the ascorbic acid and negating its effectiveness against scurvy.

By the following spring, nine officers and 15 crew members had fallen ill and died.

A second handwritten notation on Lieutenant Gore’s note, written a year after the first message, indicated that Crozier had made the decision to abandon the ships on April 22, 1848. Gore’s note remains the only known record detailing the crew’s last attempt to survive.

After being trapped in the ice for 19 months and with the original food supply nearly exhausted, Crozier calculated the men’s best option would be a 600-mile overland trek to the south of King William Island. From that point, the remaining 105 crew members would cross the Simpson Strait with hopes of reaching the mouth of the Great Fish River (now the Back River) on the mainland.

Once there, he hoped to find game and get help from a Hudson Bay Company outpost.

Ironically, the mouth of the Great Fish River is approximately 900 miles east of the mouth of the Coppermine River, where Franklin’s first overland expedition ran afoul some 25 years earlier.

The men fashioned sleds out of two lifeboats and packed them with their remaining provisions. The crew dragged the sleds down the icy coast of King William Island and on to the pack ice for their southbound journey, only able to cover 1-½ miles each day in the rugged terrain,

Out of the 105 crew members who started the last trek of the Franklin expedition, evidence indicates only 35-40 made it to the mainland.

The expedition’s disappearance set off a massive 18-year search effort that started in 1848.

Britain officially declared the crew deceased in service on March 31, 1854.

No survivors were ever found.

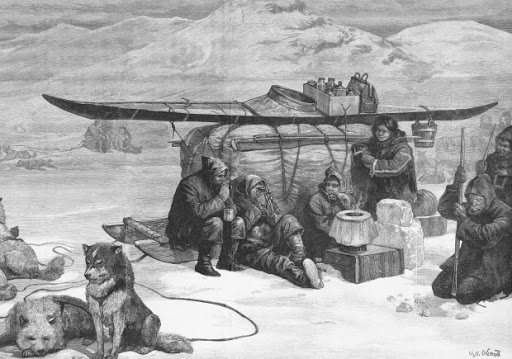

In 1854, Scottish surveyor and explorer John Rae had reached Repulse Bay (approximately 250 miles east of the mouth of the Back River) and met several Inuit families who had come to trade. Some had objects that belonged to Franklin and his men.

The Inuit told Rae that four winters ago, they came across at least 40 kabloonat (non-Inuits) who were dragging a boat south. Their leader was a tall, stout man with a telescope, who may have been Crozier. The white men communicated by hand gestures that their ships were crushed by ice and that they were going south.

When the Inuit returned the following spring, they found approximately 30 corpses and signs of cannibalism.

If accurate, this means Crozier’s band survived in near-starvation and hypothermic conditions for nearly two years after abandoning the ships and the start of search operations.

Unable to convince the government to sponsor another search for her husband, Lady Jane Franklin personally commissioned one more search expedition in 1857. Under the command of Captain Francis Leopold McClintock, that expedition later discovered Crozier’s sleds on King William Island in 1859 as well the remains of gun-room steward Thomas Armitage.

McClintock noted that there was an abundant supply of heavy goods in the sleds and observed they were “a mere accumulation of dead weight, of little use, and very likely to break down the strength of the sledge-crews.”

In 1992, archaeologists and forensic anthropologists discovered another campsite on the western shore of King William Island. They excavated the remains of what they believed to be part of Crozier’s crew.

Analysis of the bones showed cut marks that were consistent with de-fleshing and pot polishing, which takes place when the ends of the bones rub up against the inside of the cooking pot. This typically occurs during the end stage of cannibalism, “the last dread alternative,” when the marrow is extracted from the bone.

Much of what happened to the Franklin expedition was a mystery until the Erebus and Terror were found after being lost for nearly 170 years.

The remains of the HMS Erebus were discovered in 2014, followed by the HMS Terror in 2016. Both were located near King William Island.

The Erebus’ location, along with its anchor usage, seems to indicate the crew may have attempted to re-man the ship and sail her back to England.

Researchers continue to explore the wrecks and recently found Crozier’s cabin on the Terror to be well-preserved. There is potential for new documents to be discovered that could provide more clues on the expedition’s fate.

Both ships are now within the boundaries of the Wrecks of the HMS Erebus and HMS National Historic Site with limited access to the public.

Never heard of this exploration. Very interesting and informative. Enjoyed very much

Wow, this was news to me as well, very interesting story.

Thanks for sharing it!

Cheers,

Todd-